I’ve always been quite itchy about Black history in the American landscape. Growing up as a carefree and precocious Black girl in a very liberal, predominantly white town of Bloomington Indiana, I had access to a lot of unique and distinct cultures from around the world. I had peers whose native languages were not English, and I got to learn so many kinds of culturally rich traditions when spending the night during sleepovers. My blended family contributed to that learning as well. My mother and birth father were from the Deep South, Mississippi and Arkansas, respectively. My grandmother, and her mother, Big Momma, were very rooted in Crystal Springs, Mississippi—Tomatopolis of the World (I can attest that the fresh green tomatoes are some of the best)—and those Southern cultures, especially food and folk cultures, are still rooted in my family today. My stepfather, who came into our lives when I was about 4 years old, was a descendant of Irish Americans from New York State, and included us in his cultural traditions of corned beef and cabbage for New Year’s to bring good luck and prosperity, as well as introduced us to and supported our journeys in Catholicism.

It’s from these experiences, and many more, that my desire to scratch my Black history itch probably grew from. My parents always encouraged questions and explorations. Very early memories I have include visiting the many different libraries in town and being visited by the mobile library that would come to my daycares. Access to knowledge always seemed available, but understanding how to access knowledge about hidden or erased cultures became increasingly important as I aged into adulthood.

I’ve been privileged to pursue the many different educational opportunities at major institutions across the world. These experiences have equipped me with skills and tools to do deep academic research in a global environment. And yet, my greatest privileges have been the grounded, local work I’ve done over the years in communities and with community members across socioeconomic and sociocultural landscapes. Folks have invited me into their homes, to their private organization meetings, and to their intimate cultural events. These are the moments I most cherish because they feel warm and open… and real. There are the quiet moments, too, that I hold onto, like moving between spaces on trains, or driving long distances with one or two other people. These quiet moments where people share and talk and sing and reflect together. These are little doorways into the everydayness of everyday people and life. Archives are like those doorways: quiet, open, grounded, and, in unique ways, feel like you’re in a state of intellectual or emotional movement.

When I first arrived at the Berea College Archives, I wasn’t sure what I was in for, but I was told by one of the archivists to ‘forage’, likening archival research to walking through a forest with a curious mind and an unbounded sense of discovery. “Let the ‘data’ tell you what it is,” is something I tell me doctoral mentees when they embark on the early data collection of their research. And here, I found myself embracing that same sentiment: let the archival material show you what it wants you to see. “Okay, Woodson.” I thought to myself when I reached for my first box of records from his collection box.

These early archival moments gave me more questions to explore. I would eventually come to realize the way these archival figures wanted me to share their stories was through creative research and expression. It was when I put the pieces together: the research, the storytelling, the teaching, the artmaking, that the project started to form its own logic. In hindsight, it seems obvious this is the way it would go, but in moments before this clarity, I wrestled with how to get the word out, so to speak.

Then I started making the games. Nay, I got funded through the America250KY grant (thanks Kentucky Arts Council and National Endowment for the Arts!), I hesitated at that threshold for a brief moment, and then the ideas came-a-knocking at the door. The handle jiggled vigorously, a key inserted and turned the lock, and a door opened to the possibilities and ideas that would become a series of quilted table games, guidebooks, and eventual exhibition.

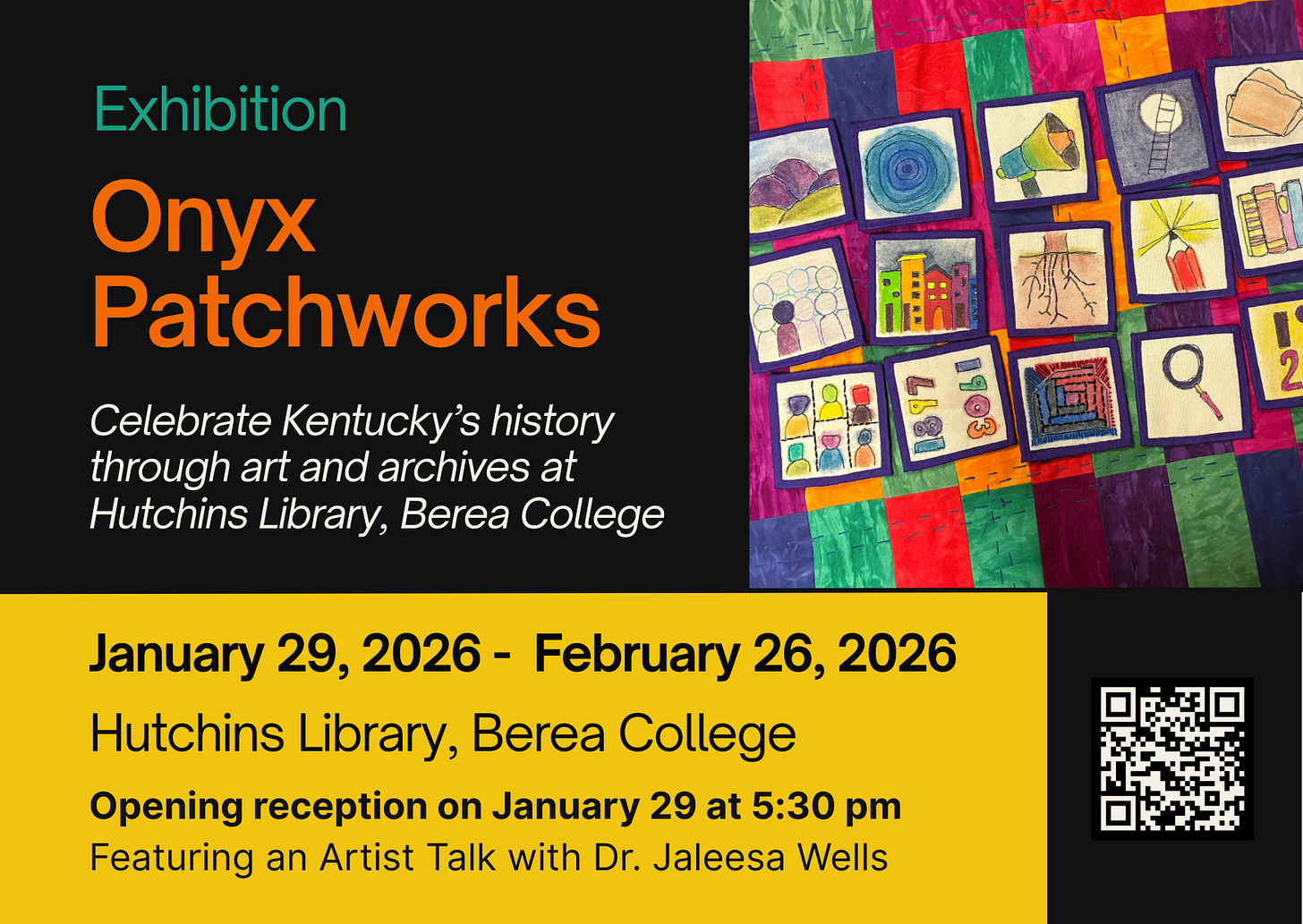

I decided to call my project Onyx Patchworks: Storytelling and Play from Kentucky’s Black Cultural Archives because it highlights the variations of Black culture in the word ‘onyx’, a gemstone that is majority black with specks of white. Some onyx stones can be different colors like red, brown, green, blue, and gray. This color spectrum and potential felt resonant with Black American culture, predominantly Black with mixtures of other cultures that define the unique Black American experience. Patchworks is a nod to quilting and crafting, but also a metaphor for how our different experiences are patched together into a quilt overlay that tells the stories of American cultures. Together, these fit the focus of my project nicely: three distinct historical figures existing in different spaces and times and yet patched together in this archive and place.

The first works I made were abstract quilt sketches, small-medium quilts (24 x 24 in) that represented the three figures: a classroom for Hooks in geometric formation, an elevation view of rural mapping for Laine, and words from Woodson’s publications configured in a spiral. I dyed fabric by hand, cut out and applied my hand drawn shapes and letters, and let the sketches move me toward visually communicating what I was uncovering in the archives.

I didn’t end up using those quilt sketches, but they taught me to get out of my head and into the fibers, considering color, shape, lines, and texture to express my discoveries. They also helped me find courage to begin thread illustrating, which is drawing with thread either by hand or machine. My thread illustrations became the foundation of the project: 4x4 in squares quilted using thread illustration and painting, and hand or machine bound with a simple border. In total, I made 108 of these 4x4 squares across the three games, with unique symbols emerging from my research.

What the America250KY award did for me was critically important in this project. It required me to share my work. Not to only make my art in a silo, but to make my art accessible and playable in my community. And over three different events, I was able to engage alumni, community members, students, and educators in game playing sessions at the archive. My quilted games and guidebooks were becoming those doorways and pathways for others.

And it was during these game plays that two things happened: one player asked what 1926 represented. I told them it was the year Woodson established Negro History Week (later becoming what we now know as Black History Month). This clicked that 2026 would be 100 years since the origins of this event. And the second thing was I started to see four shared symbols across the three games: Mountains, Ripples, Megaphone, and Classroom.

These two epiphanies created the beginning and makings of the exhibition, Onyx Patchworks: Exploring Black American History in the Berea College Archives.

Standing at this moment of clarity with the centennial realization, emerging shared symbols across the game pieces, and the way the games started to dialogue with each other, I could sense that my ‘little quilts’ project was becoming something larger than research and play. Something that wanted to be walked through, listened to, touched, seen. The exhibition began to take form in the same moment the doorway opened widely.

So, this is where I’ll pause for now and offer you another invitation to step through this doorway with me as we walk together throughout the exhibition. Each week I will share one or two articles from the exhibition, archives, and artworks. We’ll move deeper into the games and the art quilts, and, together, unravel the archival stories stitched in Kentucky and America’s cultural landscape one patch at a time.

If this article resonated, you can subscribe to follow the full six‑week Onyx Patchworks exhibition zine.

Feel free to share this with educators, librarians, artists, memory workers, and anyone who learns through story, craft, and history.